Banned books required reading at new Lake Worth Beach book clubs for kids, adults

- Sep 30, 2022

- 7 min read

ONE DAY NEXT month, a group of children will gather in a cheerful reading room in downtown Lake Worth Beach to flip through the pages of a popular picture book that, in some parts of Florida and the United States, they’re not allowed to read.

The monthly Children’s Banned Picture Book Club, geared to readers ages 4 through 7, will launch Oct. 8 with a reading of Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story, an award-winning book about how fry bread became an essential Native American food tradition after communities were forced from their ancestral lands.

Ten days after that, another group of readers will gather in the same M Street reading room to launch another monthly Banned Book Club, this one for people ages 13 and up. They’ll read and discuss the Ray Bradbury classic Fahrenheit 451, about a society where books are outlawed and burned.

Both books are among a growing collection of reading material that has either been pulled from public shelves or challenged as inappropriate by conservative groups, school districts and libraries in Florida and other states.

But they’ll be welcomed by the host of the two reading clubs — the Lake Worth Waterkeeper.

What do banned books have to do with a non-profit whose mission is lobbying and advocating for water quality in the Lake Worth Lagoon and its surrounding ecosystem?

The short answer can be found in the pages of Fahrenheit 451, about a society where books are burned to eliminate sources of complexity and contradiction to ensure uncomplicated happiness for citizens.

“I get the same reaction when I bring up cyanobacteria issues or climate change: ‘Oh, it’s not that bad. You guys are so extreme.’ They want to control the narrative, and it’s the same way with banning books,’’ said Reinaldo Diaz, who founded Lake Worth Waterkeeper in 2017.

“A lot of these books and the banning of the books itself is pretty much exactly why the government and certain nonprofits control the narrative,’’ he said.

Although Diaz was elected to the Lake Worth Beach City Commission in March 2022, the Lake Worth Waterkeeper is not affiliated with any government entity.

The Lake Worth Waterkeeper promotes its mission through public awareness programs and environmental educational initiatives such as the popular Lagoonies program for kids and young adults.

Those programs often lead to broader discussions of history and culture, said Melissa Landis, the waterkeeper’s education facilitation and development director.

“A part of that is kind of acknowledging and reading some of these books that aren't otherwise available nowadays in classrooms, like ones on indigenous people and books that talk about real history,’’ she said. “That plays a part in environmental education because we need the historical context and background to fully understand where we are now.’’

Melissa Landis, education director for Lake Worth Waterkeeper, flips through the pages of Fry Bread. (Joe Capozzi)

Since those discussions inevitably delve into deeper debates of educational reform, Diaz and Landis felt it important for the Lake Worth Waterkeeper to advocate for the discussion of banned books of all subjects.

“The Banned Book Club is kind of a response to what's happening in education,’’ said Landis. “Banned books we see as another way to talk about how education needs to change or how to look at it differently.’’

The Banned Book Club for readers ages 13 and up will decide at its first meeting Oct. 18 which books to discuss at its November and December meetings. The next two children’s picture books have been chosen.

On Nov. 19, the Children’s Banned Picture Book Club will read And Tango Makes Three, which tells the story of two male penguins who create a family together. And Tango Makes Three was the fourth-most banned book between 2000 and 2009 as well as the sixth-most banned book between 2010 and 2019, according to the American Library Association.

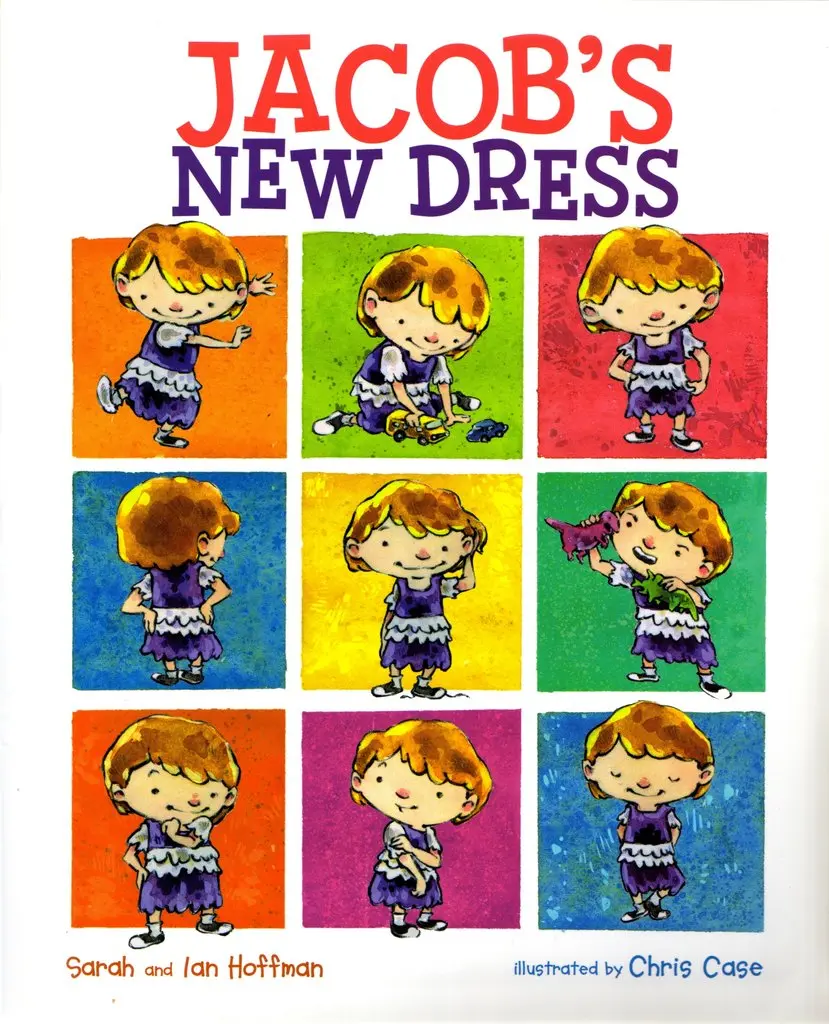

On Dec. 10, the club will read Jacob's New Dress, which addresses challenges faced by boys who don't identify with traditional gender roles. The book was pulled from schools in North Carolina.

Parents will accompany their children to the monthly Children’s Banned Picture Book Club readings, which will be led by Landis.

“We will provide context for the banned book along with some talking points that parents can take home for longer discussions at home with their children. That's kind of the idea behind the Banned Book Club,’’ she said.

“We always highly support family interactions. It's never about just the children. It's about the family and being able to experience and have those discussions together,’’ she said.

The launch of the banned book clubs comes at a time when books across the United States are coming under attack as never before.

In a report released Sept. 19 as part of Banned Books Week 2022, PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for freedom of expression, identified 2,532 instances of books being banned in 138 schools in 32 states over the 2021-2022 school year.

The American Library Association says challenges to books this year reached the highest level since the association started tracing the issue decades ago. More than 1,500 titles have been pulled from shelves, many titles disappeared secretly, outside proper procedures.

Florida ranked second in the nation for school-related book bans with 566 books banned in 21 Florida school districts, according to PEN America’s report Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools. Texas led the way with more bans at 801 across 22 districts.

The school districts with book bans are in Brevard, Broward, Clay, Duval, Flagler, Hernando, Indian River, Jackson, Lake, Lee, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach, Pinellas, Polk, Santa Rosa, Sarasota, St. Johns, St. Lucie, Volusia and Walton counties.

The book removals are just one piece in a larger, Republican-led campaign to reshape public education in America, as The Washington Post reported. Conservative lawmakers in 17 states have passed laws restricting what teachers can say about race, racism and sexism, according to an Education Week tracker.

In Florida, the book bans are tied to two new laws that have emboldened parents to speak out against library materials.

House Bill 1467, signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis on March 25, gives parents and members of the public increased access to the process of selecting and removing school library books and instructional materials. And the Parental Rights in Education bill, dubbed the "Don't Say Gay" bill by critics, prohibits school instruction of sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade.

Reinaldo Diaz shows off the reading room at Lake Worth Waterkeeper "base camp" in downtown Lake Worth Beach (Joe Capozzi)

In anticipation of the new laws, the Palm Beach School District pulled and reviewed 31 books in addition to other learning materials to make sure they were in compliance, according to The Palm Beach Post.

While the dozens of books made it back onto library shelves, those that mainly focused on gender identity or sexual orientation are now restricted to grades four and above, The Post reported.

“The trouble with this recent banning of books is that it's coming from parents and the government,’’ Landis said, “yet these are books children want to read. They are picking up these books themselves and we are saying, ‘No, we can't be curious and we can't ask questions or know about these things.’’

“At the end of the day,’’ she said, “it’s a lot of adult fear, and we are projecting it onto our youth. It doesn't need to be that way.’’

Landis is working on her doctorate degree at Prescott College, researching the historical paradigms of American public school systems and looking at alternative grassroots education as a bridge.

“The problem with our education is not that it is incomplete,’’ she said. “The omission of histories paints a somewhat fictionalized version of our American heritage and the banning of books is another form of omission.’’

Through the banned book clubs, “We can support another generation that's a little bit more, I don't want to say tolerant, but accepting of different people that are not like them.’’

Lake Worth Waterkeeper "Base Camp" in downtown Lake Worth Beach (Joe Capozzi)

The book clubs will be held at “base camp,’’ the name of the waterkeeper’s new office at 111 N. M St.

On Oct. 8, the children and their parents will not only read Fry Bread, they’ll cook and eat some, too.

Fry Bread and other books with “protagonists of color” that have been swept up in conservative campaigns, PEN American said.

“It is a book about a native grandmother who teaches kids how to make fry bread. It's literally a recipe about how to mix dough and salt and water to make fry bread, and that is banned,’’ Diaz said.

“What is it about this native grandmother teaching this cultural history that is so offensive? A dialogue needs to be had.’’

Landis said she understands some people in the community might be offended by the group’s decision to host banned book clubs for children and teens.

“Sure, there may be blowback, but I am not overly concerned. You have the option of just not participating,’’ she said.

“Lake Worth Waterkeeper is not a governmental agency. We have the ability to say and do the things that maybe other people are scared to do or are unsure of. We are making a statement about who we are and the things we believe in and one of them is advocacy for all people and all communities, and that includes the books that we read.’’

Diaz scoffs at claims by supporters of book bans that certain reading materials “may lean more toward indoctrination rather than age-appropriate academic content,” as one school board president told The Washington Post.

“Building critical thinkers is pretty much the opposite of indoctrination,’’ Diaz said. “You don't have to agree with what we are saying but you should be comfortable with having a discourse about it.’’

© 2022 ByJoeCapozzi.com All rights reserved.

If you enjoyed this story, please help support us by clicking the donation button in the masthead on our homepage.

About the author

Joe Capozzi is an award-winning reporter based in Lake Worth Beach. He spent more than 30 years writing for newspapers, mostly at The Palm Beach Post, where he wrote about the opioid scourge, invasive pythons, the birth of the Ballpark of the Palm Beaches and Palm Beach County government. For 15 years, he covered the Miami Marlins baseball team. Joe left The Post in December 2020. View all posts by Joe Capozzi.